Art as Resistance: Black Artists Who Challenged Injustice with Bold Expression

Art has always been more than just decoration—it’s a powerful tool for resistance, education, and change. Black artists, in particular, have long used their creativity to challenge oppression, amplify their communities, and inspire movements for justice. From murals to quilts to revolutionary graphic design, their work serves as both a record of struggle and a call to action.

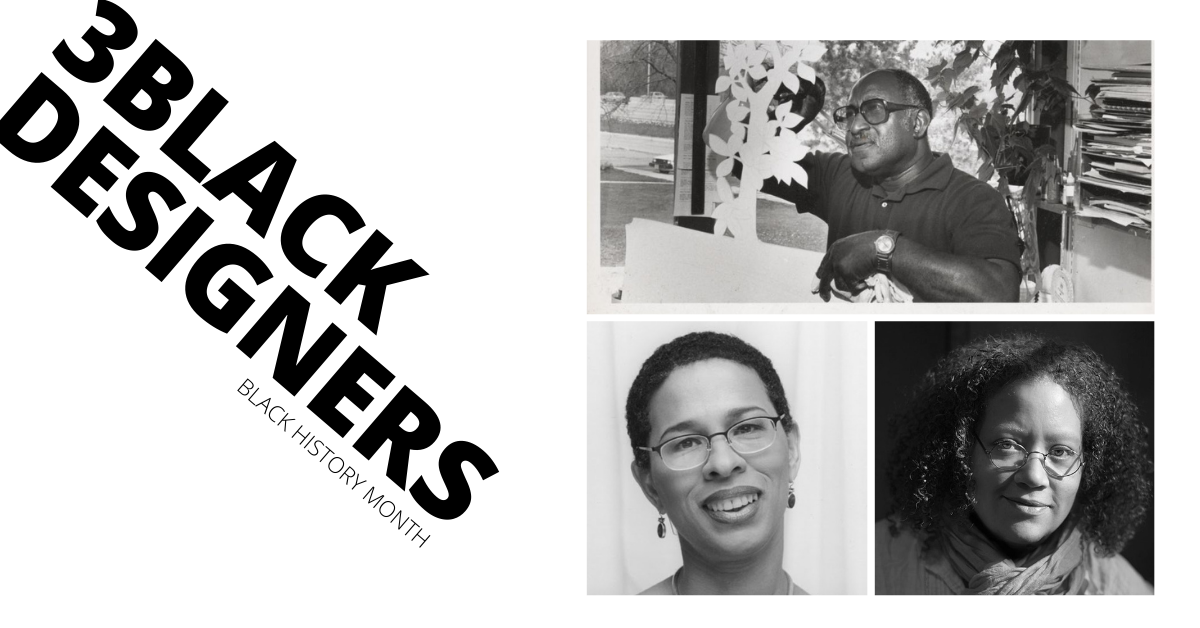

This Black History Month, we’re highlighting four groundbreaking artists—Emory Douglas, Faith Ringgold, Jacob Lawrence and Kemba Earle—whose art didn’t just document injustice but actively worked to dismantle it.

Emory Douglas: The Revolutionary Artist of the Black Panther Party

Emory Douglas didn’t just create art—he built a visual language for revolution. Born in 1943 and raised in California, he studied commercial art and graphic design, skills that would later shape the bold, striking imagery of the Black Panther Party.

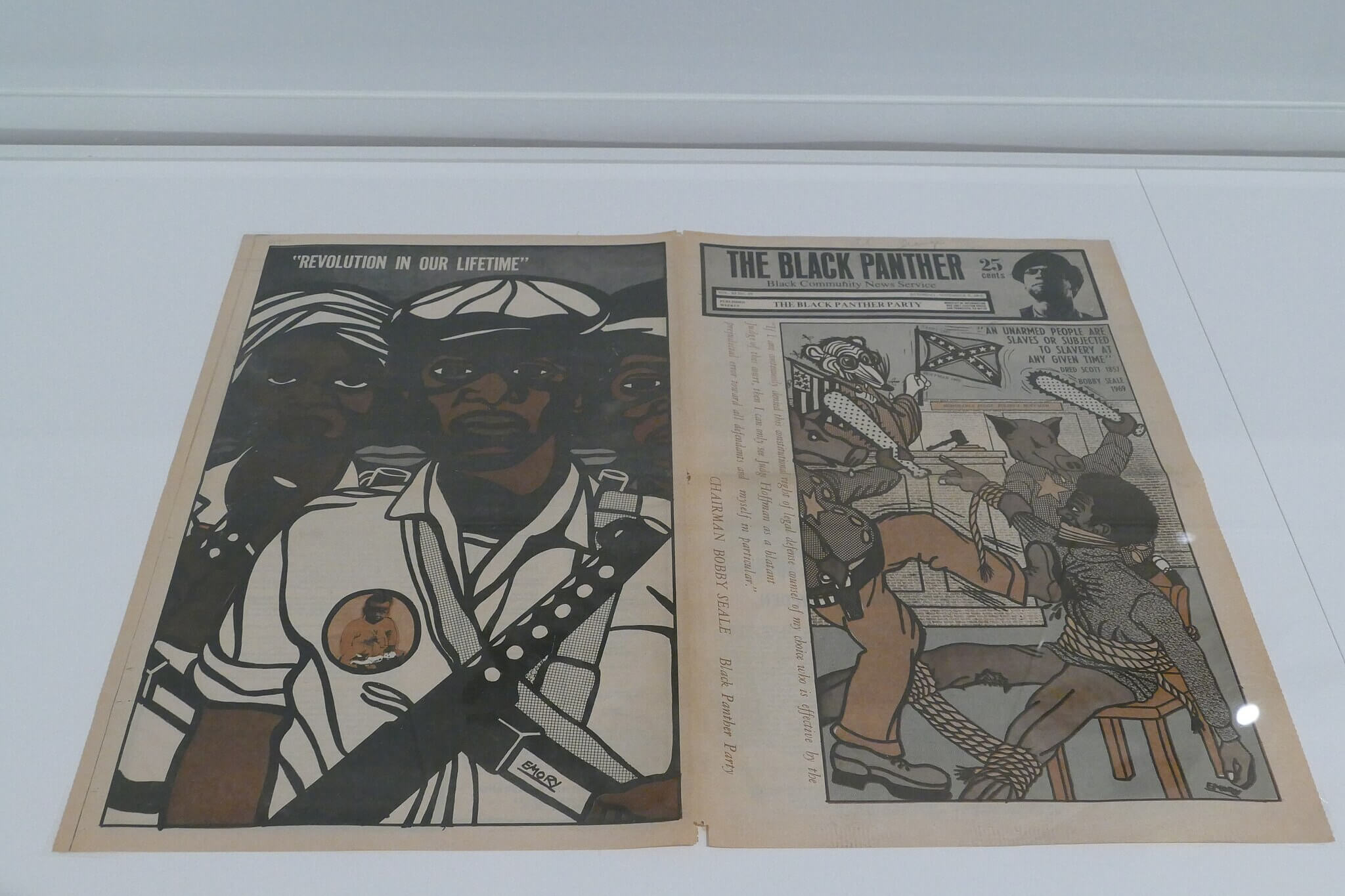

As the party’s Minister of Culture, Douglas was responsible for the radical artwork in its newspapers, pamphlets, and posters. His images depicted Black people as strong, self-reliant, and ready to fight for justice—pushing back against the racist stereotypes that dominated mainstream media. His work wasn’t just about aesthetics; it was activism on paper.

Various Works From Black Panther Newspaper by Emory Douglas

Loz Pycock, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Douglas’ designs were everywhere—plastered on walls, carried at rallies, and printed in newspapers that circulated widely. His art made the struggle visible, ensuring that even those who couldn’t read could still grasp the urgency of the movement. Today, his legacy lives on as artists and activists continue to draw from his powerful visual storytelling.

Faith Ringgold: Reclaiming Narratives Through Art and Activism

Born in Harlem in 1930, Faith Ringgold’s career as an artist, activist, and author spans decades. Growing up during the Harlem Renaissance, she was immersed in the cultural and intellectual energy of Black creatives—an influence that shaped her lifelong commitment to storytelling and social justice.

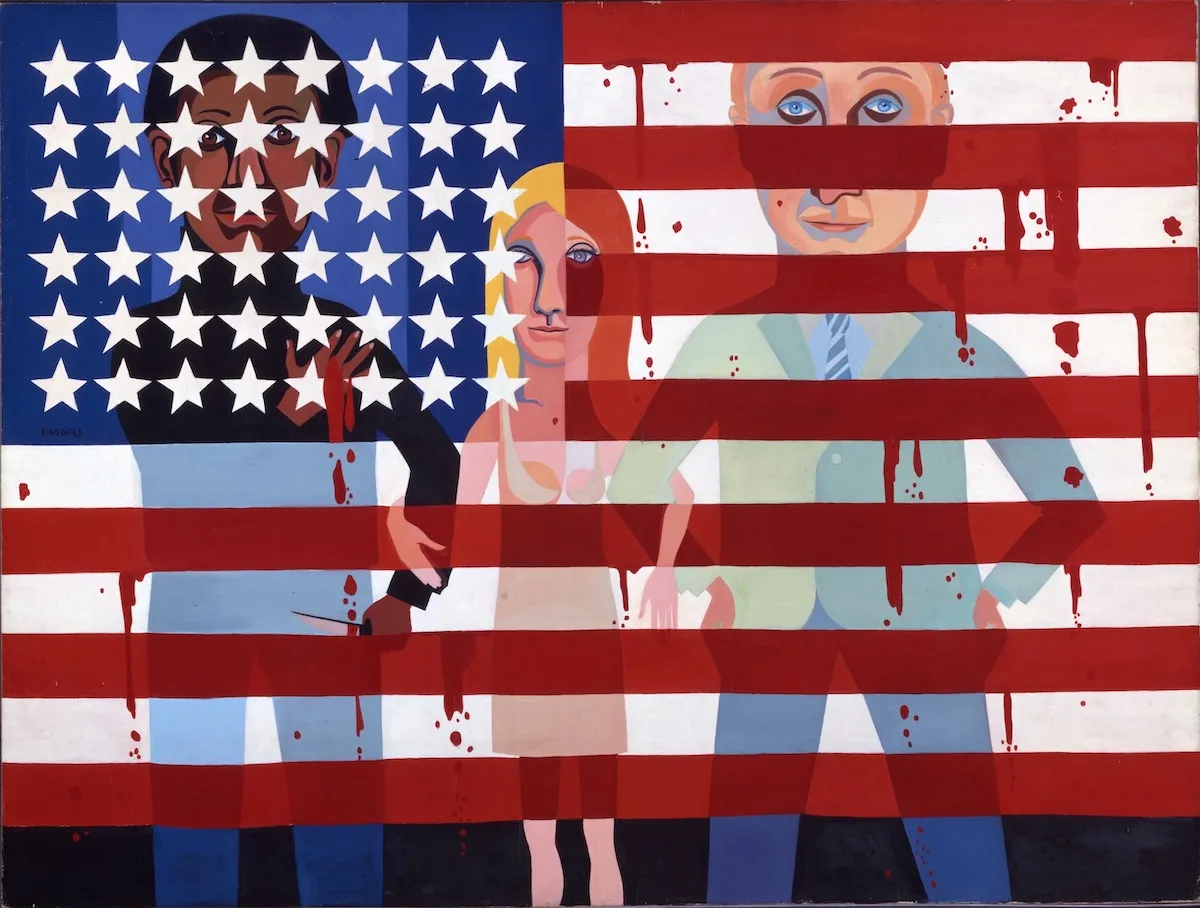

Ringgold is best known for her story quilts—a striking fusion of textile art, painting, and narrative that brings Black history to life. Her 1960s series, The American People, tackled racism, segregation, and gender inequality head-on, refusing to let these issues fade into the background.

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #18: The Flag Is Bleeding, 1967.

©Faith Ringgold/ARS, New York, and DACS, London/Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York/National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

But Ringgold didn’t just make art about injustice—she fought it. In the 1970s, she protested major museums that excluded Black artists, demanding visibility in spaces that had long ignored them. Thanks to her advocacy, more Black artists gained recognition, pushing open doors for future generations.

Beyond her visual art, Ringgold’s children’s books—like Tar Beach—continue her mission of telling Black stories with beauty, depth, and power. She reminds us that art isn’t just about what we see—it’s about whose stories get told.

Jacob Lawrence: The Storyteller of the Great Migration

Jacob Lawrence was just 23 when he created The Migration Series—a stunning 60-panel collection that depicted the Great Migration, when millions of Black Americans moved from the South to the North in search of opportunity.

Born in 1917 and raised in Harlem, Lawrence developed a unique, dynamic style using bold colors and sharp lines to capture the movement and resilience of Black communities. His work didn’t just portray history; it made history feel urgent and alive.

Throughout his career, Lawrence focused on themes of struggle, labor, and collective action. Whether he was painting Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, or everyday Black workers, his art emphasized the dignity and power of ordinary people fighting for their future.

During the Civil Rights Movement, his work took on even more weight, reflecting the urgency of the times. His art wasn’t passive—it was a rallying cry.

Kemba Earle: Amplifying Activism Through Bold Design

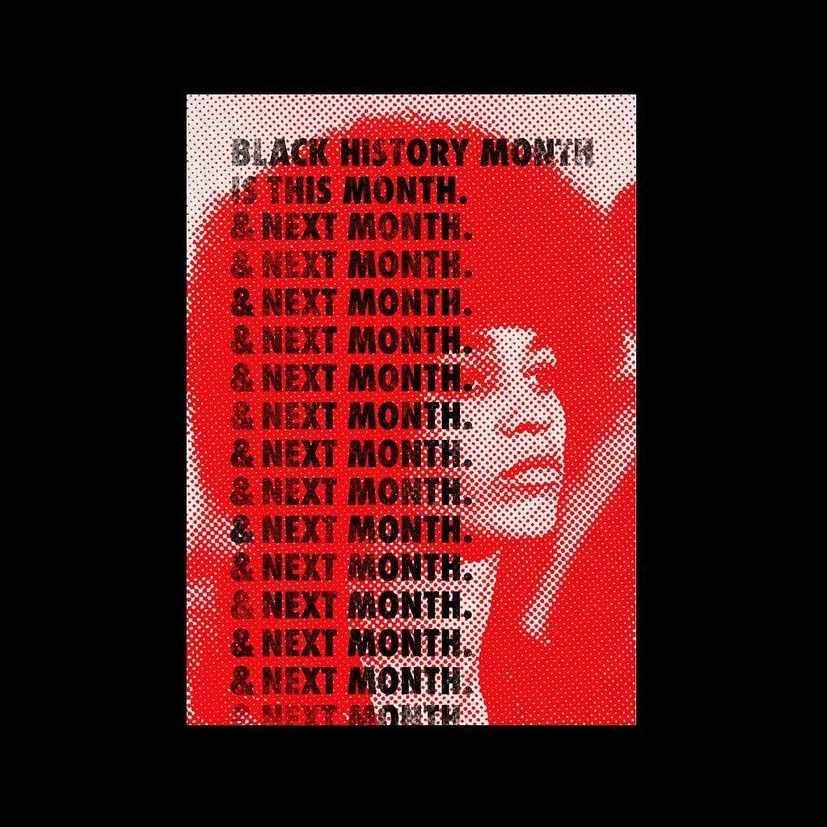

As movements for racial justice continue to evolve, so does the visual language of resistance. Kemba Earle, a graphic designer and illustrator based in Buckinghamshire, UK, is part of a new generation of artists using digital platforms to challenge oppression and amplify marginalized voices. With Caribbean and British heritage, she brings a unique perspective to her work, blending bold color, conceptual imagery, and sharp typography to confront racism, sexism, and systemic inequality.

During the Black Lives Matter uprisings, Earle’s striking posters and social media graphics became a rallying force online, echoing the hand-painted protest signs carried through the streets. Her designs, often styled like newspaper headlines or political banners, deliver urgent, no-nonsense messages—demanding justice, accountability, and systemic change. Inspired by artists like Emory Douglas and activist groups like the Guerrilla Girls, she understands that art isn’t just about aesthetics—it’s about mobilization.

Earle’s work reminds us that in a world where images circulate faster than words, design is a powerful activist tool. Like Douglas, Ringgold, and Lawrence before her, she proves that resistance isn’t just something we fight for—it’s something we see, share, and make impossible to ignore.

The Power of Art in Overthrowing Oppression

Art has always been central to movements for justice. It speaks where words sometimes fail, reveals truths that history books erase, and mobilizes people in ways that speeches alone cannot.

For marginalized communities, art is a means of reclaiming identity, documenting struggle, and imagining liberation. The work of Douglas, Ringgold, Lawrence and Earle proves that art is never neutral—it either upholds the status quo or challenges it.

From the murals of the Black Lives Matter movement to protest posters and digital activism today, we continue to see how art fuels change. The images that accompany resistance movements aren’t just decoration; they are weapons of liberation—shaping how history is remembered and how the future is envisioned.

Honoring the Legacy, Continuing the Fight

The legacies of Emory Douglas, Faith Ringgold, Jacob Lawrence and Kemba Earle remind us that art is more than self-expression—it’s a form of activism. Their work demanded a new reality, one where Black people are seen, heard, and free.

This Black History Month and every month, let’s not only honor the artists who paved the way but also uplift those who are still creating, still resisting, and still demanding change through their work. Because the revolution is ongoing, and art remains one of its most powerful tools.

We mourn the loss and celebrate the bright light and life of Dot Think Design team member Cathleen Meredith, who unexpectedly passed away in February after a short illness.

We mourn the loss and celebrate the bright light and life of Dot Think Design team member Cathleen Meredith, who unexpectedly passed away in February after a short illness.